HELLO! WELCOME TO THE PREMIER SITE ABOUT CAPT. WILLIAM BECKNELL AND THE SANTA FE TRAIL (WHICH HE BEGAN IN 1822).

Since its inception some eight years ago this site has been visited by over 50,000 people interested in this aspect of American history. Visitors have ranged from some of Capt. Becknell’s decedents to Santa Fe Trail scholars to students from some 43 countries.

INTRODUCTION

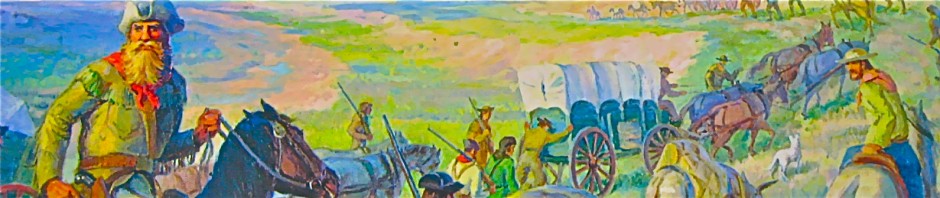

History is often influenced by seemingly random events. Such is the case with Captain William Becknell’s having taken three wagon loads of trade goods to the Mexican town of Santa Fe in 1822. Because he was rewarded for his efforts by making a large profit, paid in gold and silver coins, this got the attention of many Americans when a newspaper published an account of Becknell’s venture. And so the Santa Fe trail was born which lasted for 58 years and brought what is now the southwestern part of the US to the attention of settlers, traders and businessmen.

The fact that the US was struggling with an economic depression at the time and had recently expanded its borders to include lands west of the Mississippi River made Capt. Becknell’s experience even more timely and important.

Following Becknell’s example were an increasing number of traders and merchants from the US and, later, Mexico. This new focus upon the lands west of Missouri soon got the attention of eastern manufacturers and bankers who had previously ignored the economic potential of trade with Mexico. In turn, over the next twenty four years, they lobbied the US Congress and Washington decision makers to acquire this territory for the US. In 1846, the US began a war to seize Mexico’s lands north of the Rio Grande river including what is now New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and California. As a result, Mexico lost almost one-half of its territory and the US extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Who could have known that one man’s need for money to pay his debts could have had such a major eventual consequence?

What follows is the telling of how this major result was caused by the economic hardship of one man, his life story and the history of the Santa Fe Trail which he was the first to travel in a wagon (native Americans and animals had traveled this route for eons).

THIS SITE CONTAINS:

+ THE HISTORY OF THE SANTA FE TRAIL (1822 – 1880)

+ A BIOGRAPHY OF WILLIAM BECKNELL, THE FOUNDER OF THE TRAIL

+ PHOTOS AND MAPS OF THE TRAIL

+ A COMPREHENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY

THE AUTHOR AS BECKNELL IN REENACTMENT COSTUME

Note: As you read the replies/observations of other readers at the end of each of my pages you will probably wonder, as I did at first, why so many are not easily understood. The reason most likely is that people from over 40 countries are offering these replies. So, their syntax/sentence structure is often not the same as it would be if English was their first language.

would like to see a real pic of the real william becnell.

So would I. apparently none were ever taken. This almost a solid fact based upon the nature of photography during that era. Photography was not available as a rule in any place other than the bigger US cities until the late 1840’s. And then it was a hit and miss situation as to availability. Since Becknell died in 1856 it is very likely that a photographer did not appear in Clarksville Texas until some time after that date. Also, Becknell was 68/69 in 1856 and, even if the opportunity presented itself, he may not wanted to a picture taken due to his age.

William Becknell had a Grandson by the name of Ben Becknell and Ben Bencknell has two daughters withe my sister they are both passed on now.

The mom and dad and one of the sisters has passed on their is only child alive that i know of. but Yvonne had five children and she has more then twenty Grand children and several Great Grand children so the Becknell blood lives on, Yvonne is in her sixty’s and not in the best of health, but I pray for her every day!! Her father is from MO he lived in Clarksville TX for a while. I’m not sure how Ben Becknell and my sister go together. Thank GOD my sisters daughter still has her dads

death and military Records to prove the FACT!!

I appreciate all of the information you have accumulated about Captain Becknell. Sometime around his death, his son, John Calhoun Becknell, left Texas and came to California. I am his great-great grandson. I hope to make a trek to Clarksville in the next year or two, and will certainly try to see your presentation.

He, John Calhoun Becknell married a Elizabeth “Betsy” Guest, a relative of mine.

I to am related to the Captain! My grandfather he was like a great, great uncle from Kentucky! I enjoy looking at all this information you have posted! I originally thought that was his true picture for he looks very much like my grandfather and was disappointed that it was not! He was a true American hero and I am proud to be related!

The funny thing is my mother’s side of the family is from England and I found out that one of them William Parker in 1822 also fought in the small Blackhawk war!!!

Maybe the were friends or at least knew each other!! Just to think that both sides of my family came together for the good of this wonderful America really sets well with my heart!

I have checked your website and i’ve found some duplicate content, that’s why you don’t rank

high in google’s search results, but there is a tool that can help you to create

100% unique content, search for; Boorfe’s tips unlimited content

I grew up on the Santa Fe trail Between Independence and Raytown- so the History is important.- Enjoy visiting New Santa Fe last stop in MO before trail entered Kansas territory. Arrow ock is where my Grandfather Came from St CHarles- Te starting pint or the trail after they Crossed the MO River From Franklin. Have Driven the trail Route from its start to Independence.

Do you have any information about the Becknell slaves? My relatives are Becknells from Bagwell, Sherry, Clarksville. Also do you know if the Becknalls were related to the White family?

I have driven from Independence MO down the “dry trail” to Santa Fe. I also have driven down from Bents old fort via Ft Union down through Raton Pass. What wonderful country and reading of those wonderful people across this vast and open country in their wagon trains fires my imagination. Zane Grey first fired my imagination with his beautiful description of the countryside and in my boyhood I vowed to see this wonderful country and its history. I also have read immensely of the Civil War. What a wonderous and beautiful history that the US possesses!!!

Do you know what his black children’s names were I’m a bit and I’ll also but and I’m in Wilkesboro North Carolina I like to know what is black children’s names are because my father’s name is William becknell also and his father’s name is William Walter becknell